There is a staggering number of monthly and weekly magazines in existence. In the computer field alone, W. H. Smith shops may well have to find shelf space for as many as 80 titles. Each title has its own style and its own ‘look’. Readers may well be forgiven for thinking that a magazine just ‘happens’ every month, but behind the style and the look a lot of effort goes into it throughout many stages. This article doesn’t set out to show how every magazine arrives at your newsagent every month, we’re just looking at CRASH...

CRASH is perhaps a little unusual compared with most other computer magazines. For a start off it is not produced by one of the major publishing houses which include EMAP (Computer & Video Games, Sinclair User), Argus Specialist Publications (Home Computing), VNU Business Publications (Personal Computer -Weekly, -World and -Games) and the giant IPC (Big K, and through its Business Press section, Your Computer). All of these organisations have their headquarters in or around London. CRASH is published by Newsfield Limited, based in the small Shropshire town of Ludlow — about as far away from computers as you could imagine. But that’s one of the wonders of the home computer — they’re everywhere!

It was one of the major points in the concept of CRASH when it started a little over a year ago, that reader input would be an important aspect of the magazine, and in the light of that we have always tried to be straightforward with any comments on the contents of the publication. I doubt, for instance, that any other title in existence has had such a strong two-way dialogue with its readers over magazine aspects like spelling or setting errors, as we have had over this year! Continuing that policy of openness, we felt it would be interesting to give readers a brief insight into how the magazine is actually produced, starting from the moment one issue has ‘gone to bed.’

‘Going to bed’ might be a good place to start — it’s what most CRASH staff feel like doing when an issue is finished! But the phrase goes back to the earliest days of printing, when pages were impressed with their contents on huge machines where the text was etched onto blocks of copper laid on a solid ‘bed’ and the paper was pressed onto the inked plates by a heavy roller. Things have changed quite a bit, as we shall see...

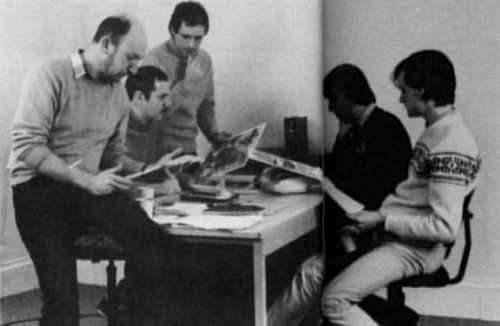

A daily production meeting taking place around the editor’s desk. Present are Roger Kean (editor), Oliver Frey (art editor), David Western (production design), Matthew Uffindell (software reviews), and Kevin Foster (assistant editor.)

As in most things, there are departments to CRASH which each have their own responsibilities. Broadly these are Editorial, Production, Advertisement, Administration and Finance. Finance falls outside the scope of this article. Editorial organises the written material, Production designs and lays out the issues, Advertisement secures advertisers and their ads, and Administration (naturally) largely cocks up everyone else’s work!

Editorial, Production and Advertisement are very often kept quite separate in most organisations, but not so with CRASH. Each issue is planned at the time of working on it, and it is important to keep all departments closely in touch with each other, often complementing each others’ efforts. It is also worth bearing in mind that although this article may make it appear that things happen in clear-cut stages, usually all the processes are going on at once — it’s chaos at times, or, as the favourite phrase would have it, ‘it’s a nightmare!’

The first thing to be decided is of how many pages will the issue consist? This is dependent on several factors like, how many advertisers are there, how many games are expected to be reviewed, how many competitions will there be, and so on. Advertising is a very important factor, because it governs the number of pages it is economical to print. In the 60s paper was only a fraction of the total production cost of a magazine. As a result it was news stand sales that made the publisher his operating costs and some of his profit. Today, paper costs make up almost two-thirds of the production cost — as a result news stand sales only account for a part of the operating costs and ad revenue has to make up the rest and hopefully end up with some profit.

Once these items have been clarified and the pages decided upon, the planning really starts. The function of the Editor (Roger Kean) is to oversee the general scope of the written material. He also writes quite a chunk of it, helping with reviews, articles and competitions. Kevin Foster is the Assistant Editor. He is responsible for incoming news items, organising competitions with software houses and making sure the details are all written up ready for typesetting. Roger liaises with outside contributors like Derek Brewster and Angus Ryall, ensuring that their material arrives on time.

Each morning there is a production meeting. This sometimes only lasts for a few minutes and involves both the editorial and the production people. It helps to keep everyone informed as to what is going on. During the first week of an issue at these daily production meetings the issue is planned out. By the end of the week the Tick Off sheet can be drawn up — we’ll look at that under the Production heading later.

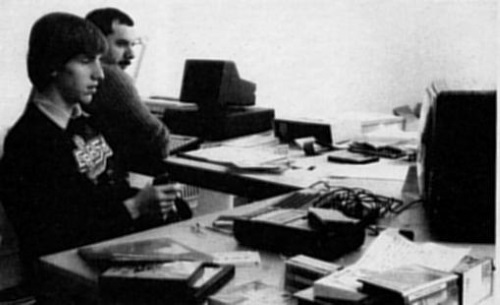

With the outside reviewer’s reports in, Matthew and Roger collate and write up the review, Spectrum and monitor sit cheek by jowl with the Apricot computer into which all the material is typed ready to go to typesetting.

One of the most important aspects of CRASH editorial is the games reviews. The process of reviewing games goes on all the while. 18 year-old Matthew Uffindell is the in-house reviewer and as such organises the other reviewers. This entails logging cassettes as they arrive from software houses and seeing that the review team get them in good time to be able to report back. CRASH has six regular reviewers ranging in age from 14 to 30 who tackle the arcade games. They come in from day to day, collect games and review report forms, returning everything when they have finished. It is a policy that at least three of them get to see every game.

When the reviews are being written up for typesetting, the introductory pieces are usually written by either Roger Kean or Lloyd Mangram aided by Matthew, who plays the game as the review is being written to double check on the stated facts given by the various reviewers.

Meanwhile, Kevin checks press releases for news material and calls back anyone if he wants more detail. He also pre-sorts incoming letters to ensure that Derek Brewster receives his Adventure Trail letters and Lloyd Mangram gets his Forum mail. The pre-sorting is a big job as many letters contain playing tips and hi-scores as well as general Forum information.

Gradually, during the three weeks of an issue, all the material comes together and is typed into an Apricot computer using a word processor program called Superwriter. The resulting floppy discs are sent to London where the typesetters do the rest.

In the early days of mass printing typesetting meant exactly what it said. From a written manuscript a typesetter actually cast the printing letters in metal (usually lead), or he already had stacks of pre-cast letters, rather like the ones you get in a John Bull printing kit. These were arranged in trays as a ‘make-up’ from which the page would eventually be printed. In fact he actually set the type. Similarly any pictures, photographic or drawn, would be engraved onto plates and set flush in with the type. Today it’s all done with computers, but the old words remain. A typeface (ours is called Helvetica) is called a font (or fount, from the word metal foundry). Adding a larger space between lines of type is called ‘adding lead’, because that’s what you did, add blank lead.

Now the information is typed into a computer and a floppy disc is slotted into a typesetter photo unit, which contains numerous different type faces, and the result is photographed onto a roll of bromide paper, which is processed like an ordinary photograph. But the typesetter needs to know certain vital things from the editorial department. These include factors like how wide will the printed column be (the column you are looking at now is a quarter column — four to the page), will it be justified (this column is justified — those in the Forum for example are unjustified, as they are ragged on the right), what point size will the type be in (this is 9 point), what type face (this is Helvetica Roman, Helvetica Bold looks like this and Italic like this. The sub-headings on these pages, for instance are in 12 point Helvetica bold condensed which looks like this). (Note: this doesn’t necessarily apply to the web version.) All this information is included with the floppy disc and the typesetter machine does it automatically. The resulting bromides are returned to CRASH for the production department. It is an early example of where editorial and production must work together, since it’s no use editorial getting a piece typeset across a quarter column if the production plan calls for a third column or half page.

Game screens being photographed off the Microvitec Cub Monitor. Recently, some magazines have taken to using screen dumps made on colour ink printers, but at CRASH we still think that the ‘feel’ of a photograph is better. The camera is usually set to a shutter speed of [?] or a second to take account of the TV roll bar. That’s why freeze frame facilities are essential for a still picture, and that’s where the Cambridge Slomo device comes in handy.

As the reviews are being written up, the games must also be photographed. This is done by Production Designer David Western. It’s quite a simple process, but time consuming, and involves the use of the excellent Microvitec Cub Monitor with a camera pointed at the screen at a set distance. Here, Matthew usually divides his time between review writing and helping with the photography, since it requires someone to play the game to a certain point, while David photographs. The Cambridge Slomo has also proved invaluable in getting good freeze frames.

The colour screens are the first to be taken because the colour work in CRASH takes the longest to prepare for printing and must be ready at least a week before the rest. It is equally important, therefore, that the editorial side gets those reviews and articles written first.

Once the photographs have been taken, processed and contact printed (all done in-house), the captions can be written for them. The black and white screen pictures are then enlarged ready for layout.

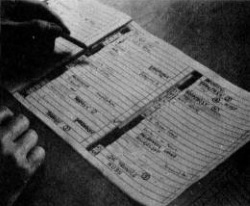

This is the ‘Tick Off’ sheet for the Christmas Special issue which you are reading. It details the pages, where colour falls, and what will happen on every page. The tick off sheet mutates as the issue progresses and alterations are made to the plan, but without it, layout would be impossible.

The heart of CRASH lies in the writing and in the layout, or design, of the magazine. It is a long and complicated business. As we have seen, it starts with the daily Production meetings, from which emerges a plan for the issue. The plan is shown as a ‘Tick Off’ sheet, basically a list of all the pages which shows where the our pages fall, and what goes on each page. It’s called a ‘Tick Off’ sheet, because when a page is totally finished ready for printing, it gets ticked off and forgotten — well, almost forgotten!

Juggling with the tick off sheet is a work of art. First of all the advertisers who have booked space have to be slotted in, bearing in mind their requirements. They all want to be on right hand pages at the front of the magazine, for instance! CRASH is printed in several sections of pages comprising of 32 pages per section. In those 32 pages there will be 16 which can be in full colour, and they fall in very specific places, which makes the juggling act even harder. It’s all too easy to end up with too many adverts one after the other, which doesn’t look good. With the tick off sheet planned reasonably well (it changes daily in minor ways due to alterations in design, or because an article ends up being longer than originally planned for), layout can start.

CRASH is laid out on grid sheets. These sheets, slightly larger than A3 size, contain two pages side by side, pre-printed with pale blue lines which denote the maximum page size (A4), text area (so that there is a neat margin all round) and other details like the vertical quarter, third and half page columns for lining up the text.

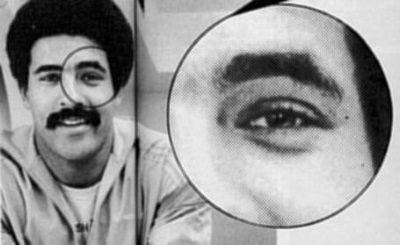

You may think that the pictures on these pages are photographs. In fact they are not, because a photograph is made up of a range of greys. These pictures are made up of black dots. In this example, the circle area of the picture has been blown up to show the black and white dot structure. All photographs in magazines and newspapers are done in this way. The dots are created photographically in the process camera by using a plastic screen made of very fine, regular dots. It is called ‘screening’ and the result (which is a PMT) is usually called a half tone, whereas the original photograph is called a continuous tone.

The bromides which have arrived from the typesetters containing all the written material, are trimmed and stuck down on the sheets. It is here that the real skill comes in, because the typesetting must be cut up and arranged on the page in an orderly and pleasing manner, leaving room for pictures and captions. At the same time the photographs must be slotted in. A photograph is referred to as a contone or continuous tone, meaning it is made up of every element of grey, from black through to white. The printing press won’t be able to cope with this, as all mono printing is literally only black and white. Before it can be stuck into position on the grid sheet, the photograph must be converted into a PMT which stands for Photo Mechanical Tint (a tint is lots of regular dots). This is done on the Process Camera, a machine which can reduce or enlarge a photograph through a fine optical screen of tiny dots. The resulting bromide looks like the original. but is actually made up of thousands of black dots of varying size (see picture). This may then be stuck down in position to complete the page.

A set of advertiser’s film separations on the light table. The four pieces of film carry information to be printed in Magenta, Cyan, Yellow and Black. The production department only has to ‘tag’ these with a piece of paper bearing the page number on which the ad is to appear, and send them on to the printer.

Another function of the production department is to ensure that advertisers’ material arrives on time, in the correct state, and goes off to the printer. In the main there is little production work to be done on ads, as the advertisers should have already done it all. It merely remains to attach a piece of paper to the film containing the ad and write on it the page it should appear on so that the printer knows. But in some cases additional work is required. This may be minor, like the alteration of the advertisers’ colour code which tells him what issue of which magazine the coupon came from. Sometimes it may mean doing quite complex process work on the process camera to get the ad into a fit state for printing.

We do some of the more simple editorial work in-house, but most of it has to be sent to London, to a specialist house. Pages with colour have the text stuck down and are marked up to show whore the colour transparencies should go. Modern high speed colour printing is done using only four colours — Magenta, Cyan, Yellow and Black. Any colour photograph must be scanned and separated so that film is produced for each of the four colours. The film is, of course, in black and white, and contains the photograph in the form of a PMT, i.e. thousands of dots. A set of four pieces of film containing the page is known as a set of separations, because the four colours have been separated from each other. When each of these four layers is printed one on top of the other in register in its proper colour, the result looks as if it is in full colour just like the original. It is in this form that advertisers’ film should arrive.

Eventually all the grid sheets are laid out, complete with their headings, text, captions, pictures in PMT form, page numbers and any illustrations and they are almost ready for the printer. The artwork in CRASH is done by Oliver Frey. While the issue is being laid out, he will be painting the cover, the comic strip Terminal Man, any other colour work that is required, and adding small black and white illustrations where David has left room for them. His colour work also gets sent off to the specialists in London to be scanned and screened and planned together with any text.

The Process Camera. Artwork or photographs to be processed are placed on the copy board at the bottom, under a plate of glass. A vacuum is applied to keep everything absolutely flat. Powerful lights either side illuminate the artwork. On top is another vacuum head. Here the bromide paper or film is placed onto which the artwork is to be photographed. Sometimes the bromide paper onto which the image will be projected is placed face down on top of a plastic optical screen of dots to make a PMT or ‘half tone’.

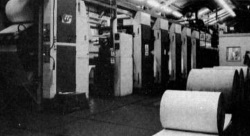

Most magazines today are printed on high speed Web Offset machines, which are enormous. The web refers to a vast, continuous roll of paper, big enough to print 8 or 16 pages simultaneously on either side. Offset refers to the fact that the image on the printing plate is inked, makes contact with a roller, the image is transferred to this roller, which then contacts with the paper — in other words the plate and paper never actually make contact, they are offset from each other.

The plates, which are strapped into the printing press, have been made from film.

CRASH shoots its own mono film. This simply means that the grid sheets containing two completed pages are placed under the process onto a similar sized sheet of photo film. The result is a black and white negative. The process camera does not ‘see’ pale blue, so any of the grid sheets’ lines used for layout, do not photograph through. Colour is done similarly, except there are the four-colour film sheets for each page, and these are usually contacted back to make a positive image on the film (which is easier for the printers when it comes to lining up all those dots in register between the four layers).

All this film, including the advertisers’ film is sent to the printer, in our case Carlisle Web Offset in Cumbria. There they take the film and stick together pages in blocks of 8. The 8 film plates then get laid on top of specially photo-sensitised plates and exposed to ultra violet light. The film image is transferred to the plate, and whether it is from negative or positive film, the image on the plate comes out as a positive. These flat plates are then carefully positioned on the printing press and rolled into a drum. The Harris presses are capable of printing about 30,000 copies an hour, and the pages come off the press already folded, so that several sections can be slipped one inside the other ready for stapling and final trimming.

From the printer the bundles of CRASH are delivered to carriers under instruction from Comag, the distributors of CRASH. Before the issue is printed Comag, will have done all the work necessary to ensure that news trade wholesalers have got their orders in. This is what decides the actual print run.

This is one of the Harris-Marinoni Web Offset Presses at Carlisle’s plant in Cumbria. Left foreground is the paper tower which carries the rolls of paper (some of which can be seen on the right). Beyond the paper tower you can see the five ‘heads’. Each ‘head’ carries two drums around which the plates are wrapped and the offset rollers which transfer the inked image to the paper. Thus both sides of the paper are printed with 8 pages on either side. The first four ‘heads’ are for the colour pages, the first one prints the Cyan, second prints the Magenta, third prints the Yellow and the fourth prints the Black. The fifth ‘head’ prints the mono only pages. Beyond the five printing units you can just see the oven through which the paper passes. This bakes the ink dry before the roll passes into the folding station (not visible) where the roll is automatically collated (16 pages of colour and 16 of mono), folded into a finished section and roughly trimmed. Later the other printed sections will be added, stitched and trimmed to the finished A4 size, bundled in 50s and delivered to Comag, distributors of CRASH.

As you can see, there is quite a lot that goes into producing an issue of CRASH every month, and this is only scratching at the surface. An important administrative area is liaising between printer and distributor to get the print run right. Put simply, magazines sell through news agents. The news agent is stocked by his local wholesaler, the wholesaler gets his copies from the distributor, who organises the whole machinery. To keep track of everything Comag uses computers extensively, not only for accounting purposes, but also for collating information relating to demand, so that publishers like CRASH can see where sales are good and where they are not so good.

But another important administrative area is internally seeing that everything happens when it should, and this includes dealing with the Hotline and competition results.

Administration also has to look that we get paid for advertising, and don’t get burned fingers from companies like Imagine, who can run up enormous bills without paying them. It’s a fine balance.

In only another few days this issue will be going to bed, and a new year will be arriving. There is always a rush at Christmas time to get magazines through printers who are packed to capacity, and this one has been quite a big issue. By the and of this week, as it comes to shooting the film, most CRASH staff will be repeating the old phase ‘It’s a nightmare!’ But a few days after that, they’ll be knuckling down to the first issue for 1985 — it never stops!