When the original Imagine bubble burst back in the summer of ’84 the company’s employees became redundant overnight. From the ashes and confusion rose a phoenix, Denton Designs, a programmer’s co-operative set up by Ally Noble, Steve Cain, Graham ‘Kenny’ Everitt, John Gibson and Karen Davies — essentially, the team which worked on Imagine’s ill-fated ‘mega-game’. The company produced a number of innovative games, including Shadowfire and Frankie Goes to Hollywood, and quickly earned a reputation for original, high quality software.

Early this year the jungle drums of the software industry beat out a rumour: the Denton Design team was breaking up. Apparently, the founder members had peeled away from the company to pursue their own interests. So what did happen to Dentons? Julian Rignall travelled to Liverpool to find out what went on, and what’s going on... original programs are getting a bit scarce nowadays — licences seem to have taken over.

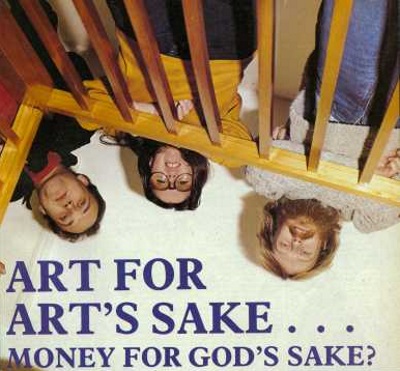

The first port of call was the offices of Denton Designs, situated in the heart of Liverpool’s equivalent to Harley Street. Although only one founder member remains, graphic artist Ally Noble, the new Dentons is still very much a co-operative consisting of six people: Ally, John Heap, Andy Heap, Stuart Fotheringham, Dave Colclough and Colin Parrott. The company is alive and kicking. So what happened during the so-called split?

‘The directors, Steve Cain, Karen Davies and John Gibson all wanted to go freelance’, Ally Noble explains. ‘They didn’t really want to work with the company, but wanted to work for themselves. At the time it looked as though everyone was going to pack in and give up, but we decided not to.’

John Heap takes over the story, ‘I think they were a little disillusioned with the amount of profit actually going into their pockets and they reckoned they could get twice their wages if they went freelance, which I think is true. After they left there were rumours saying that the Denton Designs team bad split up, so we sent out lots of letters dispelling the rumours that Dentons had died. We were back in business within a week.’

Which rather implies that the people who remained behind are less money orientated and, perhaps, see games designing more as a labour of love...

Ally points out their philosophy ‘if we wanted more money we’d all go freelance and drive around in our Porsches.’ John chips in: ‘I think you really have to commit yourself, especially when you consider how much time you actually put into the game. When you weigh the effort against the money it’s really just a pittance that we earn.’

Denton Designs is a name that has become associated with original material — a reputation the new team intends to build on as Ally explains: ‘we see ourselves as people who are here to do our own stuff and not things like conversions.’ John continues: ‘when you’re working on a game the idea for the next one starts forming in your head. Ally agrees, ‘yeah, and then it gets bounced around the office. The idea for Bounces came out of Frankie. I think the whole thing is a sort of progression.’

John is currently doing a lot of background reading into a game set in Ancient Egypt. ‘We tend to do a lot of research into our games. You get more into it if you do. Ally says, ‘for the Great Escape I watched the Colditz series and went out and bought a load of military models.’

It’s all very well coming up with brilliant game designs, but surely the sheer volume and complexity of ideas must be limited by the target machine’s capabilities? Spectrum programmer John shrugs his shoulders, ‘it’s a bit like racing a Mini instead of a Porsche. You can only go so fast but you can become better at driving the Mini than you are at driving the Porsche. You can get just as much fun out of driving the Mini fast as you can driving the Porsche faster...

‘I’d like to do a 128K game,’ he admits ‘not just more screens, but I’d like to push it like you push a 48K Spectrum. It’s the same processor and same machine it’s just the graphics potential is much bigger — bigger sprites and map size. It’s really sad at the end of a 48K game where you want to put in a few extra little tricks but you haven’t got the memory.’

Ian, a Commodore programmer, joins in. ‘With the C64 it’s a case of finding new tricks you can do with the machine, but it is annoying to have to throw out ideas because you can’t get the machine to do them.’ Stuart Fotheringham, another Commodore specialist, agrees: ‘the big problem with the 64 is the actual speed of the processor.’

John laughs. ‘If you look at the Commodore you have sprites and all that and you think ‘what am I going to do with them’. On the Spectrum you have none of those, so the actual thought about how the machine is to be used is much more diverse — you get things like Knight Lore. If the Spectrum had died a death and the Commodore was reigning supreme I don’t think you’d ever get anything like Knight Lore games.’

John mentions Knight Lore with a certain amount of respect. Do the DENTON members pay attention to other games on the market? John: ‘Not much really, we’re not really games players. We’re a bit insular really.’ Ally takes over: ‘we went to the PCW Show and there was nothing which really impressed us. Oh, the title screen on Alleykat, that was nice.’

In response to the question ‘which DENTON game were you least pleased with?, Ally instantly retorts ‘definitely Transformers... it’s really a personal thing, we all like different products, but I think Transformers was an embarrassment’. ‘We were a bit over a barrel and we had to do it.’ John admits, ‘There wasn’t much you could do with the subject matter of the program... we did our best.’ Nobody says anything about Roland Rat...

So why don’t the DENTON team launch a label in their own right to avoid Transformers type problems? Ally shakes her head...

‘We don’t know anything about marketing,’ John says. It boils down to money: ‘there’s also a problem with cash flow — we wouldn’t get any money for six months, and we’d have to pay people in the meantime. We may do something like that in the future with one game perhaps being financed by another company. We don’t really know all the tricks and all the wheeling and dealings. I think we’re all a bit naive really.’ There may be room for compromise, as Ally explains: ‘we wouldn’t mind trying some joint publishing, where we put in the development and somebody else puts in the marketing skills and then split the profits half and half. I think we’d have to get a lot bigger, though. Small is good.’

If small is good then John Gibson, programmer of Gift to the Gods, Cosmic Wartoad and Frankie, has gone one better. After splitting from Dentons he pursued a solo career under contract to Ocean.

‘I’m mainly doing licensed programs now, he reveals. ‘I’d like to do original programs, but Ocean seem to be dead wary about releasing original games — you’re guaranteed to sell a licensed product. If you want to do an original product it’s got to be very convincing. I don’t really like doing arcade conversions — they’re nearly always pale imitations of the original — there hardly seems much point in doing them.’

He’s just finished work on Galligan — so why does he do conversions if he sees so little point in them?

‘When I started five years ago I did it because it was what I enjoyed. Now I tend to think more about the money than the art form. Mind you, that wouldn’t stop me for working for less if the job made me more enthusiastic.’

Was the break from Dentons a good move?

‘Oh yes. I’ve got rid of the responsibilities of looking after other people. If anything goes wrong I know it’s my fault. It’s a bit lonely, especially when I’ve been working alone in my flat for a couple of days, but I do go down to DENTON and CANVAS for a bit of company. I suppose that’s what I miss. When Dentons started it was a very close-knit company. I was one of the founder members, and a Director. It was great when we started, and we had loads of ideas about being a software development house.

‘At first it was like us versus the rest of the world, but after a while both Steve and I got disillusioned. There was too much turmoil in the office with too many meetings. All I wanted to do was write programs and I felt that I was getting too wound up by the difficulty of running a company. I did want more money, so when David Ward of Ocean, after approaching me several times, made me an offer I couldn’t refuse, I left.’

So money, or rather lack of it, seemed to be at the root of the Dentons split. Was this the case with the rest of the original crew? It was time to travel eight miles up the Southport road to visit CANVAS, a regular haunt for the other three original Denton Designers...

Located above a large supermarket with a carpark that is apparently the source of a significant proportion of Liverpool’s crime figures, CANVAS is a new company set up by Steve Cain and ex-Argus Press Software programmer Roy Gibson. Recently they contracted ‘Kenny’ Everitt to develop the Atari ST version of Star Trek (for Beyond) and Karen Davies, like CANVAS founder Steve Cain, regularly freelances for the company.

Steve explains the financial motives that lay behind the Dentons split: ‘The thing at Dentons is that we couldn’t, as individuals, earn enough money for ourselves. Looking back, at the time of the split, we really had no choice. Dentons cost too much — it was a bit of a luxury and self-indulgent. I’ve been a lot happier since.

‘Originally the idea was to wind the company up, but we handed it over and now it seems to be doing really well. We did some good stuff which I’m proud to have worked on, and they’re doing good stuff now. Some of the guys they’ve got there now are brilliant — Colin Parrott is a genius. But I felt I just couldn’t work with them any more.

Kenny airs his view. ‘At Dentons we were making X pounds. Now we’re working for ourselves, we’re making X times three. The theory with Dentons was that we’d take on a load of extra programmers and we’d make money out of those programmers. We’d get so much money from employing them we’d be able to pay the overheads, pay them and there would be a hit left over for us. In practice we were subsidising the extra programmers. Although we haven’t got a public reputation now, the people that matter know who we are. As long as the publishers know who I am, I don’t give a toss about the public.’

Karen Davies looks rather perturbed, and exclaims ‘that’s not a very nice thing to say...’

Unrepentant, Kenny continues... ‘Yeah, but it’ll never be like the pop industry. Jeff Minter’s about the only exception, but then how many people bought Colourspace? It doesn’t matter what you write, it’s what sort of licence you get. Look at Bounces — that has eight frames of animation when the player falls over. Nobody noticed that — it was dead smooth cartoon animation and nobody noticed it. Nobody cared about the flicker-free animation. Things like that are so annoying.’

Turning to the function of CANVAS, Roy explains what the company aims to do. ‘We are a commercial programming agency — we don’t really intend to do our own stuff, not straight away at least. What we’re about is doing conversions for other people. We just churn away. Perhaps next year we’ll have enough money in the bank to allow us to take the chance and do something original. At the moment we find coin-ops the best thing to do — our artists can start work straight away and everybody else knows exactly what is expected of them.’

‘At the moment, we don’t have the reputation that Dentons have. We’ve been talking to companies such as BRITISH TELECOM who have given us stuff to do like Star Trek — now that’s a stepping stone for us.’

‘Anonymity isn’t a thing we’re really bothered about, not this year. Why should we splash CANVAS all over a licensed conversion? An original program we’re working on at the moment, Wizard War, will go out with our name on it. We might even publish it ourselves, we don’t really know... we’ll have to see how it goes.’

Kenny Everitt agrees. ‘It’s just like the early Dentons stuff which went out with a miniscule credit on it. Any customer would have thought it was produced by David Ward.’

Were they pleased with Frankie? Steve replies ‘it was nice being the programmer, but the hassles in doing it were tremendous, it practically broke Dentons.’ ‘Frankie was really original, different....’ Kenny adds, ‘I’m not blowing Frankie’s trumpet especially, what I’m saying is that there is really nothing else like it’.

‘The problem with doing your own thing is that it’s all down to a matter of personal taste. I think Bounces is the best thing I’ve done. Gameplay wise it was far superior to Frankie or anything else around at the time. As a two player game it was brilliant, but it was a marketing failure. The Spectrum version of Bounces was a complete load of rubbish — the difference was about three months of playtesting.’

Steve continues the story behind the DENTON days. ‘We got into a bit of trouble over Transformer with Ocean which we managed to do in the end — we were all under so much pressure. I designed it, so I take all the blame for it. It was the worst game Dentons ever did, and it was the biggest seller. That tells you a lot about the computer industry doesn’t it?’

Roy continues on the licence theme. ‘Licence deals annoy me. We lose directly in proportion to the size of the licence. If you’re on a royalties deal publishers screw you substantially. What they say is ‘we’ve got a brilliant licence and are guaranteed 100,000 sales, therefore we’ll pay you less royalties because you don’t need them.’ You ask for a lump sum and they say they haven’t got enough money left over because the licence cost so much, so their priorities are ‘pay for the licence, then worry about the programming’ — so how can the game be any good?

Steve doesn’t totally agree... ‘I think the only good licence I’ve seen recently is Cobra. The graphics are really bloody great but the game hasn’t got much to do with the film. Frankie was another one, a lot of thought went into that. The software industry could be generating brilliant characters and licensing them out to films and TV, but look what happens. We end up having to write a game about some crappy American TV series. It’s the wrong way round.

‘Licences do take money out of the industry which should left in. I’d like to get out of games and move into the film industry using videos and computers and all that stuff. That’s what I want to do...

Money had a lot to do with the Dentons split. The individual programmers who came together to form the original Dentons are still working within the industry, and we can expect some interesting products in the near future: it’s just the motivation behind the programming effort that has changed — in some cases, quite radically.

But the split was an amicable one — at both Dentons and CANVAS it was difficult to decline invitations to a Mega-Party scheduled for that evening which everyone from the original Denton Designs crew had been looking forward to.

Sadly, I had to make my excuses and leave. Shame really, everyone said it was a great party...