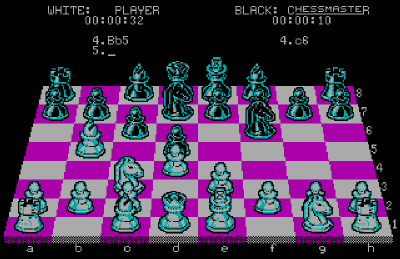

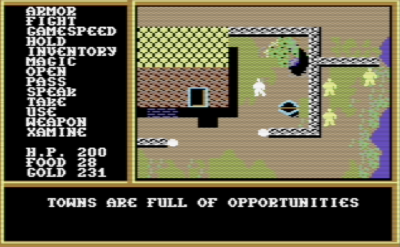

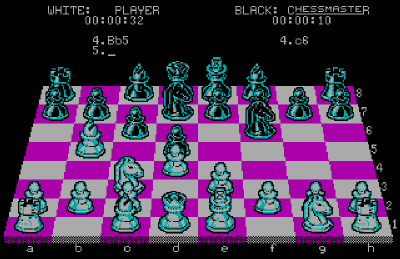

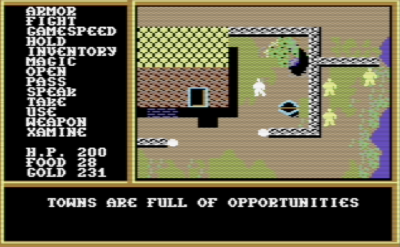

Every home should have one: Electronic Arts's polished product includes The Chessmaster 2000 (above; PC screenshot) and Legacy Of The Ancients (Commodore 64 screenshot)

Last month CRASH brought you Trip Hawkin’s balls — the Nerf Balls, little sponges which Electronic Arts bureaucrats throw at each other to relieve nervous tensions after going into the rough in another golf simulation.

But there’s more to EA than, well, little sponges. There’s quality, aggression and a massive release schedule — some dozen Spectrum titles and more for 16-bit machines — behind the American giant’s push into Britain, which starts this autumn.

There’s also a new approach to selling (and creating) software which could make or break EA’s European experiment.

And there’s the wit, wisdom and statistics of boss Trip Hawkins, ever so faithfully reproduced in this exclusive interview with BARNABY PAGE.

Every home should have one: Electronic Arts's polished product includes The Chessmaster 2000 (above; PC screenshot) and Legacy Of The Ancients (Commodore 64 screenshot)

ELECTRONIC ARTS — the very name suggests William M ‘Trip’ Hawkins, 33, founder, President and pundit. His expansive talk and his expanding corporation, which officially launched its European operation at The PCW Show, are shot through with an American approach to games software: the programmers are artists (his word), the products are elaborate and finely-tuned coffee-table C64-oriented jobs, many of them sophisticated battle/vehicle/sports simulations or adventure/role-playing games (RPGs).

Hawkins is careful not to offend his European counterparts, now rivals, too much — The PCW Show, where he held forth over pastrami salad and Coke, was evidence enough of a flourishing industry here- but quietly he criticises a stale atmosphere in the software world. ‘My initial impression of the show is that everyone seems to have coin-op licences and imitations of someone else’s coin-op licences,’ he observes. ‘There needs to be more innovation.

‘We need to raise the standards rather than continuously having lower prices and the same rubbish.

‘But if you have a programming genius trying to be managing director, you’re going to have problems.’

That’s why EA’s 220-strong team (almost 40 of them in the European headquarters in Langley, Berkshire) works like a film studio. Level-headed producers coordinate flighty artistic programmers, providing technical help and business management. There’s no in-house drudgery, no programming production line.

‘They’re more motivated when they’re independent,’ he says, ‘and we should try to be a company that helps a programmer do the things he doesn’t want to do.

‘The kind of people that are good team players make good employees; that’s very different from being an artist. An artist has to have the nerve to do something really crazy.’

Crazy? EA’s product shows little of the offbeat imagination that you can find in British games, from Manic Miner to Head Over Heels; instead it’s polished, snazzy, high-tech.

Apart from the CRL and Nexus games which it’s distributing (they’re ‘affiliated labels’), EA itself will release four Spectrum titles this winter. They are PHM Pegasus, simulating a ‘warship of the jet age... so agile... so deadly... so fast’; Arctic Fox, featuring a ‘deadly tank of the near future... a three-dimensional battlefield... accurate simulation of tank movement’; and Bard’s Tale I, a complex computer RPG.

But Spectrum conversions are a pain in the disk drive for Hawkins’s multinational, because the market is almost entirely in the UK. Is it worth EA’s while converting games for this anomaly of a machine? Yes, says Hawkins, promising some 12 Spectrum releases from EA and its two affiliated labels in the next few months, not least because EA is already supporting a Japanese NEC-type machine similar to the Speccy.

‘It’s unfortunate,’ he concedes, ‘that there are so many different models. Converting a game is like changing a Mercedes into a Rolls-Royce — you have to get out a hammer and start banging around. We really need to have a standardised computer. If every TV was different and they couldn’t receive the same broadcasts it’d be untenable.’

Still, ‘even with ambitious projects like Chuck Yeager’s Advanced Flight Trainer were going to try to bring them to the cassette market. Anyone who’s observant, if they see what’s on Commodore cassette that’s a good idea of what’ll be coming on Spectrum.’

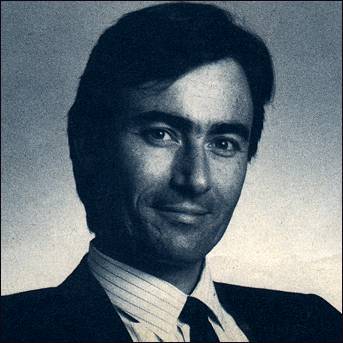

Showbusiness indeed: Electronic Arts boss Trip Hawkins puts the Hollywood into computer games

So POSSIBLE EA Spectrum titles include Apollo 18: Mission To The Moon, The Chessmaster 2000 (superchess), Skate Or Die, Lords Of Conquest (super Risk), Test Drive and Train Escape (‘more than just the greatest fast action arcade fun’, apparently) as well as some more soothing sports sims, Mini-Putt and World Tour Golf.

It all sounds rather cool, calm, professional; not crazy at all; grown-up, in fact.

Trip Hawkins has an answer. The average American games-buyer is 27, he says. (As a point of reference, the average CRASHtionnaire respondent is just over 16.)

And he says computer games have to compete with mainstream entertainment: films, TV, recorded music. The software industry has to be more than a quirky backwater.

‘The subject matter of software must be more suitable for adults. I don’t think adults are so interested in blasting away aliens...

‘If you look at movies, TV, books, it’s about real life, it’s about real people in human situations.’

There are about 50 million home computers in the world, Hawkins wildly estimates; but there are well over 100 million video machines. ‘With much better, cheaper, realistic software you could get 100 million computers,’ enthuses Hawkins.

‘And half the world’s women — we haven’t made a lot of software they’re interested in yet.’

He’s pinning down the problems. For Trip Hawkins’s new age to dawn, with a mouse in every pot and a joystick in every garage, leisure software must be CHEAPER, MORE REALISTIC and EASIER TO USE and, of course, there must be a STANDARD MACHINE. (You can imagine him at the blackboard.)

His objectives are consistent. IBM PC-compatibles are the single best-selling family in the USA, and one analysis (by Wharton Information Systems) expects almost 400,000 to be sold in the UK in 1987, Hawkins expects a boom in cheap PC-compatibles; there’s your standard machine.

In the USA, 16-bit machines already account for half of micro sales. And ‘as computers become more powerful they will become easier to use because they’re more realistic. The digital sound on an Amiga is about FM-broadcast quality.’ There’s your realism and user-friendliness.

But digital sound occupies so many megabytes of memory that Hawkins’s superrealistic machines will have to use CD-I, the ‘compact disc-interactive’ technology announced in March 1986 which will allow home micros to read CD data. A CD can store far more information far more accurately than a cassette or floppy disk.

EA has been licensed by CD-I developers Philips and Sony to use the new technology; EA is building a CD-I emulator; Hawkins expects a hardware prototype in early 1988 and, with luck, a machine on the market by Christmas 1988, when it will possibly coincide with digital audio tape (DAT) supplanting CDs on the cutting edge of sound recording. We live in an age of progress.

In Hawkins’s ideal world, CD-I and other new technologies could be ‘brought back to the mainstream computers which sell better’. And, of course, CD-I would integrate a conventional CD player with a micro; one step on the computer’s way to the centre of home entertainment.

Perhaps that’s the point, the integration as much as the technical development: ‘You’d be buying more than just a computer,’ says Hawkins. ‘I don’t have any problems with the word ‘computer’, but for some people it has a negative connotation.

‘There’s still a lot of missionary work to be done — people who like computer games feel embarrassed about it. People think it’s silly — I think they’re silly,’

But the illusion of silliness, of computer games as just another phase of adolescence, may be fading. A report published in July in Time, the influential American newsmagazine, said that nearly 40% of American executives polled ‘used their office computers for entertainment’. (Admittedly, the poll results came from software house Epyx.)

And there is joy at Electronic Arts over every sceptic who’s converted. Trip Hawkins in visionary mode: ‘Playing is the best way to learn. Every other species of mammal, that’s the only way they learn, they don’t go sit in classrooms and read books.

‘So if you’ve got a flight simulator like PHM Pegasus you’re getting a much better idea of what it’s like to be in a situation like that — it’s role-playing and so on, but it’s dynamic and exciting.

‘The simple process of interaction is good for your mind, and whatever the subject matter of a game is it makes you think about it. I get involved in reading books from playing games.’

And ‘it’ll be really mainstream when a computer is a social thing like TV or hi-fi. People listen to music, go to movies together. Software can be very social, it can teach you a lot about people.’ Hawkins’s beloved ‘average household’ has the TV on seven hours a day — if only games could take some of that time...

Hawkins draws fine lines between educational software — the stuff of CRASH Course — EA’s self-improvement software, and empty entertainment. ‘We don’t go out of our way and say we’re going to teach people something as a course,’ he explains, ‘though there are a lot of companies in the USA which do that, they call it curriculum software. (EA itself produces software for schools and colleges.) A lot of educators are snobs about computers and software, they’re pedantic.

‘Almost every new medium was introduced through a young generation — in the Fifties TV was a family purchase so kids could watch it, and then in the Sixties when rock and roll came along it was for the kids.’

He doesn’t exonerate all games from the charge of silliness, though, ‘Shoot-’em-ups are good for relaxation, but if that’s all you did it would become a negative thing — if all you’re doing is shooting things, killing things and blowing things up.’

Hawkins founded EA in 1982 with just two million dollars (about £1.2 million at current rates); it was, publicity says, ‘the 136th entrant into the home computing field’ (whatever that field comprises). Its first software was shipped in May 1983. (An early investor was former Apple Computers boss Steve Wozniak; Hawkins had worked at Apple for four years. EA was — still is — based in San Mateo, near San Francisco in northern California, near Silicon Valley: Hawkins was born in San Diego on the Mexican border, in the showbiz south of the state, Thus he applies technology to entertainment.)

EA wasn’t ready then to go multinational. For two years, 1984-1986, its product was distributed here by Ariolasoft.

But the company has grown apace. After making a pretax profit of five million dollars (£3 million) on 30 million dollars (£18.4 million) revenue in 1986, EA expects to pull in 50 million dollars’ (£30.7 million) worth of sales this year.

And late last year Hawkins reckoned it was time to cross the Atlantic and see if what works there works here.

His utopia is unlikely to be realised without bitter fighting in battlefield Europe. Hawkins is directly challenging Activision (already an archrival Stateside, where EA dominates the sales charts; now a growing force here after its recent return from four years in the red and the success of Enduro Racer and The Last Ninja), Ocean, Elite and Mirrorsoft, EA is not entering the budget market, because Hawkins believes quality commands its price.

One vital outlet, Boots, has already been lost. Since the controversial collapse of Creative Sparks Distribution (CSD) in July, Boots has been supplied entirely by Centresoft — and Hawkins doesn’t want EA/CRL/Nexus product going through Centresoft. He has two reasons.

First, Centresoft would ship games manufactured for the UK to continental Europe — but Hawkins wants to handle each country separately, with different prices and translated packaging. (He has already signed deals with distributors in seven other European countries, though the quite important Italian market hasn’t been touched despite its American-style Commodore 64 emphasis.)

‘It’s not that we don’t like Centresoft,’ he explains, ‘we want English-language product in the country where it belongs.’

Second, Hawkins wants EA to deal directly with retailers, an unprecedented move cutting out the distributors entirely. (The only distributor handling EA product is Terry Blood Distribution, which will put its games on the shelves in John Menzies and WH Smith.)

Indeed, that’s one of the reasons EA signed up its affiliated labels CRL and Nexus; they can ‘concentrate on product and make more product and better product’ without worrying about distribution, and EA will have enough different titles to impress the retailers.

‘Now the interest in signing on other labels has diminished,’ says Hawkins. What we really wanted was a critical mass so we could go to retailers with an attractive range.’

Why?

‘We don’t do this direct sale thing because it’s the be all and end all, we do it because it has to be done.’

Why?

Well, by talking to the retailers themselves, EA can cultivate loyalty to its labels, ensuring better point-of-sale marketing (ie advertising in the shop itself) and more orders.

And you guessed it — there’s also a philosophy. Hawkins wants to see bigger, better software shops like bookshops, divorced from the quite different hardware market. ‘In the early days of hi-fi records and record players sold together, now they’re separate and it’d be ridiculous to buy them in the same place. I’d like to see more stores really committed to software and stocking a broad range.’

It’s an integrated view: of how games software is programmed, debugged, fine-tuned, packaged, distributed, advertised, sold, played, regarded. If EA succeeds in the UK, it will change the way we think about games (this high-tech hyperbole is getting to me). As the the EA poster says, Unleash the power of your imagination...