JON BATES investigates the FB01 tone module and an essential editing program

A fair-sized chunk of your correspondence (always welcome, but I can’t guarantee a personal response) puts the emphasis firmly on budget. In other words, how little do you have to spend to rival Messrs Jarre and Gabriel? Well a nice way to extend your Spectrum is to start with a tone module.

A tone module/generator is in effect a sound synthesizer or sampler without any visible means of playing: a keyboard of sorts. It depends on a midi signal to stir it into life, sent from either a separate keyboard or a sequencer.

What are the advantages? Well, a tone module is usually cheaper than an equivalent synthesizer with a keyboard. There are fewer bits to pay for, so you get a little more for your money. And because tone modules are remote-controlled, they’re more flexible.

Unless you have something like the Cheetah MK5 Keyboard you’ll only be able to play and write for a tone module from the Spectrum, but if your keyboard skills are limited that’s not too bad.

And there are programs that allow you to write music in either graphic or traditional notation, such as Ram/Flare Music Machine (which will give you sampling as well) and the Cheetah Midi Sequencer.

You can connect the midi-out port on the 128 to the module and write your tunes in the rather laborious code it requires. But without an interface your control of the module will mostly be through midi channels, note commands, patch changes and velocity commands.

I’m sure that with enough devotion you could write some software — but it would be limited, as some jerk at the design stage forgot to provide a midi-in option. It’ll be difficult to use a tone module from the 128 without an interface.

Tone modules come in a variety of shapes, sizes and costs. Often when a synthesizer is launched, the tone module follows a few months later — the same synth, but without the keyboard and with far fewer buttons on the front. On closer inspection you’ll find the buttons are multifunction, and though a bit fiddly they’ll allow you access to most of the synthesizer.

Points to ponder if you’re thinking of splashing out on a tone module:

Prices start from around £275 for a Yamaha FB01 or Casio CZ101 and go through the £700 bracket for basic samplers; the complete TX rack system from Yamaha would start at several grand and end with you handing your chequebook back to the bank manager and wearing out sets of kneepads while craving forgiveness. Watch this space for details of samplers and synths as they appear.

The FB01 looks a fair bet, you might think. It uses the FM system of synthesis. (And if you haven’t heard of this, where have you been for the last four years?) It comes with 256 presets and lots of voice configurations, which means you can talk to it on any eight midi channels, and provided you ask for only eight notes in total you can split them up pretty well as much as you want — assigning pitch bend and number of notes per voice, and then committing the setup to a separate memory. Hence the term ‘voice configuration’, there are 20 in all.

The output is in stereo with limited panning facility.

Lots to play with — but you can’t make up your own voices from the FB01’s controls, and it has the usual disadvantage of a tiny LCD display which allows you to peek at only a very small part of the settings and voice banks etc at a time. And you can’t name any of the voice configurations you have created.

That is, it had these problems till now. Behold the FB01 Editor, written by Martin White (originally for himself) and used via our adaptable friend the XRI interface. For £29.95 you get a very comprehensive voice editor, voice configuration display and three banks of new sounds.

Usually when programs have been developed for the personal use of the programmer there are great gaping holes in them. Not so here — it’s easy to use and well thought through, and the manual is helpful.

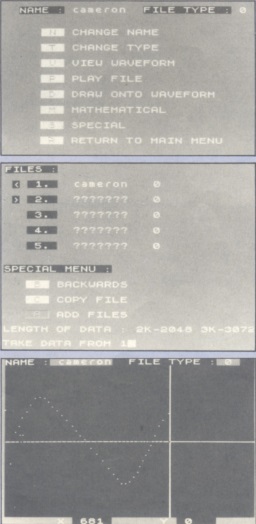

On loading you get the menu; Voice Bank Editor — Voice Editor — Configuration Display — Save And Load.

The Voice Bank Editor dives into the FB01’s voice banks, arranged in seven groups of 48, and lists them. You can reorder these, copy, delete or rename them and then dump them back into the FB01. You can select one voice and take it away for modification, or start from scratch to create a voice in the Voice Editor.

You hear the voice by playing on the numeric keys — access to all octaves is available through an octave-shift key. But for some reason it kept jumping back to Octave Three instead of the octave I was working on when fine-tuning the sound — which could be bit aggravating when you’re editing a bass sound, say.

There is a facility to alter the velocity sensitivity and hear the result — very useful, this, as many sequencers will transmit individual note velocity. You can’t play the voices from another midi device/keyboard at the same time as you’re editing on the Spectrum, but that’s a minor problem.

Sound editing is done numerically. I find this a pain — I like to have bar graphs and waveforms in front of me, as I respond to visual images better than to rows of numbers. But it was pretty easy to use, though perhaps it should display the algorithm shape, critical to the way sounds are edited. (The manual has the shapes, at least.)

You can name your new voice and put it anywhere you like. The FB01 displays ‘Dump Received!’ when any Information is transmitted to it. It’s all very easy to use even for someone who hates numbers.

Configuration Display shows you graphically what’s going on as you assemble or swap voices and assign notes and midi channels to them. The configurations are created using the front-panel controls of the FB01. You can also put a name to the configuration, which is far better than the anonymous ‘user 1’ that would otherwise appear on the LCD.

There’s also an option which will convert voices either way between a DX100, 21 or 27 and the FB01 — a thankless activity which takes hours to do manually. The conversion feature has been lacking in other Yamaha voicing programs.

The voices that came with my review program were very well thought out and covered a wide range from ethnic instruments to percussive sounds — useful additions to anyone’s sound library.

Save And Load is to tape, micro drive, or Opus One disk.

If you’ve been uncertain about Yamaha’s low-cost tone module, I’d say this program makes the prospect of adding an FB01 much more favourable. A for effort, A for results. If I were the author I’d try flogging the FB01 and programmer as a package...

PS The Casio CZ101 programmer, also from XRI, was reviewed in these hallowed pages back in Issue 38 (March 1987) — make a comparison.

Next month there’ll more suggestions on keeping the costs down and the quality up, and I’ll answer a few letters (honest!).