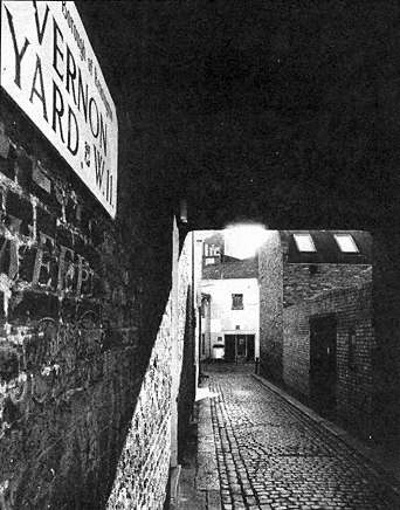

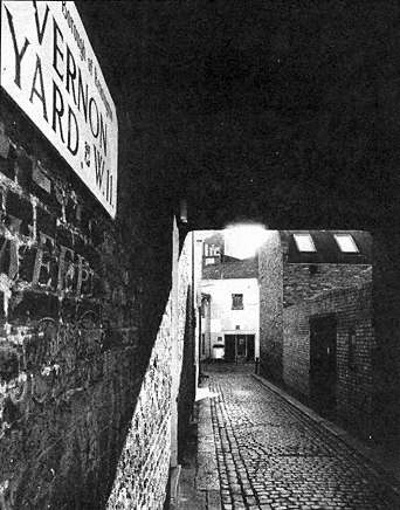

At the end of a dark alleyway, off London’s famous Portobello Road antique market, lies the Virgin Mastertronic offices

Lloyd’s mailbag is constantly brimming with letters wanting to know how you go about getting homegrown software published. The producer of most debut-programmer games is almost certainly Mastertronic. CRASH talked to Mastertronic’s Andrew Wright and asked him exactly what happens when your entrusted package lands on the doormat of their London offices...

At the end of a dark alleyway, off London’s famous Portobello Road antique market, lies the Virgin Mastertronic offices

When Mastertronic started off in 1984 they weren’t the first to promote budget soft ware, CCS had already tried that, but they were certainly the first with the marketing muscle and sheer quantity to make a success of it. At that time, a lot of the smaller software houses were going bust, providing a rich source of cheap games to launch Mastertronic’s budget range. But at the same time Mastertronic were interested in getting games from first-time programmers. There was little delay in these arriving, and the cardboard box where the games were filed on arrival was soon dubbed the ‘Magic Postbox’.

Five years on, the budget market has become massive, with budget titles usually dominating the Gallup top twenty. A sizeable proportion of these games are written by new programmers, and indeed this is virtually their only hope of getting published. With the near extinction of smaller, independent software houses most full-price software is now published by larger companies like US Gold and Ocean, which rely on established programming teams. Moreover, these software houses tend to base games on big licenses, and expect any full-price release to be available on all formats — maximising the effect of advertising.

But if getting a game published full-price is vastly more difficult now than in 1984, the opportunities of getting a budget game release are much better — although the standards are rising all the time. To attract more games Mastertronic made the ‘Magic Postbox’ nickname official six months ago, with ads in all Mastertronic’s budget releases. As a result, the number of games arriving has increased to around thirty per week on all formats.

When a game arrives in the Mastertronic offices it’s usually loaded that same day by David George, Mastertronic’s 17-year-old playtester. The selection process begins: the biggest cause of rejection is simply that the game won’t load! Games will also be rejected if they use a utility like Incentive’s Graphic Adventure Creator, or the Shoot ’Em Up Construction Set on the C64. Similarly an indifferent Manic Miner clone will soon be sent back to its creator. All games received by Mastertronic are returned, even if they lack enclosed postage, together with a form letter of rejection — or a note explaining that it wouldn’t load.

Some games, however, are so obviously excellent that it’s obvious they’re right for the label. In that case Budget Labels Product Manager, Andrew Wright, will phone the programmer the next day and try to arrange a contract.

More often, promising games are put in a box to be put through a slightly more formal review procedure. These are held whenever there’s enough games to justify a meeting. Besides Andrew and David, also present are the software producers; Tony Smith, Andy Green, Alex Martin and Nicole Baikioff. These four are responsible for overseeing the development of ‘outside’ programs, a job they are particularly well suited for as they used to be the Gang of Four — who wrote Dan Dare (92%, Issue 32) and Dan Dare II (74%, Issue 49). The marketing department may also be consulted.

Quite often a game may be brilliantly playable, but still be rejected because it isn’t likely so sell. According to Andrew, kids ‘want guns’n’violence. What’s hot now are ninjas, skateboards, death and tie-ins.’ One Gauntlet-type game was rejected by Andrew as being old hat, but Code Masters picked it up and made it more attractive by slapping a ‘ninja’ title on the game. Substantial changes to gameplay are rarely considered. The quantity of games submitted is such that Mastertronic has no time for promising games which need more than minimal changes. Some games require nothing more than the signing of the contract before being published, other games require gameplay to be tweaked.

The essential point of a contract is the signing over of the programmer’s copyright to the publisher — in this case Mastertronic. As Lloyd pointed out last month, whether you write a computer program, a book or a song you automatically have copyright on it — the sole right to make copies. The only problem is how do you prove in a court of law that you actually are the programmer, if someone does make copies. The cheapest way is simply to enclose your program in a package, seal the package securely and send it by registered delivery to yourself. As long as the package isn’t opened it should prove you had a copy of the program on the post marked date — weeks before Mr X claimed to have written it.

With a new programmer Mastertronic will usually ask that the copyright be sold to them forever, more established programmers may set a limit of a couple of years after which they get the copyright back. In return for getting the copyright Mastertronic will promise to pay a royalty on every copy of the game they sell. On average your royalties will amount to several thousand pounds!

Typically a publisher will offer an advance on this money to keep the programmer happy until the game is published. Advances vary substantially from programmer to programmer, and all have to be paid out of the eventual royalties, but they are not returnable — if the games doesn’t sell, you don’t have to give the advance back.

As part of the contract, Mastertronic usually ask for worldwide copyright, so they can sell the game abroad as well. If you want you could exclude a certain country, but this could reduce your advance and obviously decrease the amount of money you stand to make from Mastertronic sales. Mastertronic offer good opportunities to authors over US publication since they directly publish in the US, so the author gets his royalty cut direct. If the game were published by another publisher, he’d only get X% of the UK publisher’s X% cut of the US publisher’s revenue.

Sadly, however, the US market for Spectrum games is virtually nonexistent — which brings up the subject of conversions. If a title is suitable for other machines, Mastertronic could suggest conversions — these are particularly useful for boosting a game’s chart position. If you can’t write the conversions yourself you could allow Mastertronic to have them written. When these are published you’ll get royalties on them too — after the cost of conversions has been taken out.

Mastertronic argue they offer a very good deal, and if a programmer won’t accept Andrew often gives phone numbers and contact names at other software houses.

If a game is perfect as it is, and no conversions are required, it can be rushed onto the streets in three week’s time. Artwork can be done in a day or so, although some take longer, and sometimes an inlay will be dropped on the verge of being printed — as happened with Advanced Soccer Simulator.

Most games require tweaking though, and sometimes title music will be required. If the original programmer cannot provide this it may be written by a freelance musician. In fact potential binary maestros are welcome to submit material to Mastertronic for this very purpose. Graphic artists, however, are unlikely to be used as this is expected of the original programmer.

Once a game is published the programmer can continue writing budget games, or even full-price ones, sometimes going on to be a part of established programming houses like Binary Design. More common, however, is the teenager who writes one game then goes on to college or university where there’s no spare time to write another game. Star Farce (58%, Issue 61) was apparently programmed two years before its release as a version of the arcade game Star Force. When its programmer was down on his grant at university he simply improved the graphics then sent it in. He has no plans to write anything else.

One company which deals with many of Mastertronic’s conversions is Activemagic, which serves as an intermediary between four Yugoslavian programming teams and British software companies.

The head of the company is a former engineer in Yugoslavia’s merchant navy — Milan Stajcic. After emigrating to the UK, Milan got a job with Mastertronic as merchandising manager. He left Mastertronic just eighteen months ago with the aim of setting up Activemagic.

According to the Yugoslavian government there are around a million personal computers in the country, over half of which are in the home. Of these between fifty and sixty per cent are Spectrums, most of which have been bought by people visiting neighbouring European countries. Buying a Spectrum in Yugoslavia would cost about three times as much as in Britain.

At the moment the biggest software publisher in the country is Suzy Soft, a subsidiary of the State record publisher. Its games cost around £1.50, but by far the most popular tapes are illegal compilations of pirated Western games. Obviously this doesn’t do much to support the publishing of more and better games, and Milan is trying to stop it by putting pressure on the computer’s three computer magazines. Already one of the magazines has stopped carrying ads for pirated material, and the result should soon follow suit.

The first Western games to be legally published in Yugoslavia are Mastertronic’s, who have recently signed a deal with Activemagic for the latter to handle distribution of all their products throughout Eastern Europe. Games for Yugoslavia will be produced by Ljubljana, one of Yugoslavia’s ten TV companies, and will have identical packaging to the UK versions apart from Yugoslavian text. Once a proper budget market has been established, Milan hopes to bring out full-price games, for which there’s potentially a very large market.

The author of Mastertronic’s latest football game is Steven Hannah, a 19-year old native of Kilbride, Scotland. Steven started programming five years ago when he first bought his Spectrum, and has started writing numerous games but the only one he’s completed is Advanced Soccer Simulator (reviewed this issue). This was originally a BASIC game, which was rewritten in machine code to make better use of memory, up the graphic standard and generally speed things up. This version was completed by late ’87.

Getting the game published, however, ended up taking longer than the programming. Firebird rejected the game, and when Mastertronic didn’t respond after a few week Steven thought they had too. Then Andrew Wright phoned to offer a contract. Apart from a few tweaks to gameplay, and a change of title, the game was ready to be published. At one stage review copies of the game were sent out, but then withdrawn when the release date was moved back to allow the cover art to be redone.

One of the latest, and best budget puzzle games is Mindtrap (reviewed this issue) and was written by a 17-year-old Yugoslavian named Predrag Beciric. The title comes from when Predrag first had a Spectrum, ‘the whole of my family, in which I include a dog, kept telling me the computer is a trap which will eventually trap my mind’. This seems to be true since, apart from the Sex Pistols and Art of Noise, Predrag claims to be only interested in computers. The computer he most wants, apart from a Cray, is Steve Job’s NeXT machine complete with optical disk. Unlike Steven Hannah, he remains enthusiastic about games, and hopes to eventually set up his own software house. His favourite game is Atic Atac, and at the moment he’s working on a conversion for Activemagic.