Just about every known technique has been used to protect Spectrum software against copying. This month Tech Tips looks at (and hopefully), through Lenslok, the latest trick to reach the Spectrum marketplace. But first, Simon Goodwin puts protection into perspective...

Spectrum software has always been protected to try to stop illegal copying. The aim is to make the code run straight away, so that copiers can’t save after loading.

Many early programs were saved as CODE, partly to make them hard to copy with a normal SAVE command, and partly to give the impression that the program was written in machine code when in fact it was probably written in BASIC.

At the start of 1983 the first ‘clone’ programs became available — programs to read any tape into memory and dump all of the data back onto cassette. These programs hit the software producers hard — a cloned copy was as good as the original, having come directly from the computer. Clones could be used to make any number of further copies, whereas tape-to-tape copies were inferior, and could only go through two or three generations before the hiss and distortion added at each step made further copying impossible.

The first response was to increase the size of the files to fill all the Spectrum’s memory. This defeated the simple copying programs, which were ‘crowded out’ of RAM, but it made loading slow and created technical difficulties for the supplier. The pirates soon caught up and wrote programs capable of copying even a 48K file.

Software houses retaliated by re-defining the way in which programs were stored on tape. Spectrum files are written in two parts: a fixed size ‘header’, containing the file name and other details like its size; and a second part containing the data itself. Clone programs use the information in the header to work out where to store the rest of the file. This approach is foiled by the ‘headerless file’ — a short program is used to load a file with no identifying header. Without the header a simple clone program can’t copy the rest of the file.

Another approach was to encode ‘extra’ information on the tape. One simple trick was to record a brief period of silence onto the tape, between one file and the next — this quiet moment on the tape can be detected by simple software to read the cassette port. Most clone programs ignore gaps and pack files together on tape. Illegal copies can be detected because they are missing.

One Dk’tronics program used a short ‘tune’ at the end of the tape, immediately after the program. The sequence of notes was ignored by copiers, since it did not form part of the file, but the program checked for it and crashed (pretending there had been a loading error), if the notes were not present. The whole tune lasted for a fraction of a second, so it was almost impossible to detect the notes by listening to the tape.

These tricks worked, in the sense that they put off the majority of casual copiers, but there was a constant battle between the authors of protection routines and clone programs — in some cases these were the same people!

The root of the problem was the ease with which cassettes could be copied, and Sinclair responded by borrowing an idea from Atari. That US firm was the first outfit to publish computer games in chip form — on plug-in cartridges. Sinclair produced the Interface 2, an adapter to allow the Spectrum to accept cartridges.

This idea failed, for a host of reasons. Unlike the Atari, the Spectrum already had a well established, reliable and fast cassette interface. Interface 2 was expensive; it included a pair of joystick ports, but these were not compatible with many games.

The cartridges themselves cost more to produce than tapes. They took a long time to manufacture and were limited to a 16K capacity, regardless of the memory of the computer. Programs were becoming more and more sophisticated — few software houses were willing to shoe-horn their next megagame into 16K.

A few games were converted for the format, but nothing new was launched on cartridge, again denying users any reason to buy the ROM interface. Mikro-Gen have recently relaunched the idea at a more reasonable price, but it seems unlikely that Spectrum ROM games will ever take over from cassettes — the performance improvement is too marginal.

Meanwhile, trick tape schemes became more and more devious, and increasingly irritating for the producers as well as the would-be copiers. Then Software Projects came out with Jet Set Willy, a game that used a quite different system of protection.

The JSW tape is quite easy to copy, but there’s a colour-coded table printed in the cassette inlay. When the program is loaded it displays a row of randomly coloured blobs — these have to be matched up with the table, and appropriate keys must to be pressed before the game starts. The system has several snags — it is irritating for legitimate owners of the game, who have to go through the same ritual every time they want to load their copy. It is also a major obstacle for those with poor eyesight or grotty TV’s. And the colour-coded chart turned out to be quite easy to copy — once the colours have been written as letters it takes less than 10 minutes to copy the whole chart, and the job can be done several times over in the course of a boring lesson!

So software houses went back to tinkering with their tape recorders. The next step was to completely change the way in which programs are recorded, by re-defining the tones used to represent each bit of information on the tape. This approach allows programs to be loaded more quickly, since the tones can be more densely packed onto the tape.

Thus the first of the so-called ‘Hyper-loaders’ came into being. They have a big weakness. They are often unreliable — the densely-packed tape is more prone to the effects of duplication faults, and some early systems used high-pitched tones which could not be reliably reproduced by cheap tape players.

Many software producers deliberately made their systems intolerant of uneven levels or background noise, in the hope of detecting tape-to-tape copies. This lead to loading problems for legitimate users of original tapes, and Hyperloads gained a bad name, both with retailers and customers.

At this point software producers were pretty stumped. They’d fiddled as much as possible with the two component parts of a software package — the tape and the documentation — but they still couldn’t stop photocopiers and tape-to-tape copying. They’d tried to by-pass the cassette altogether, but ROM cartridges had failed because they were too expensive and required special equipment (Interface 2).

What they needed was something cheap, small (so that it would fit into a cassette box) and hard to copy. Unlike Sinclair ROMs, it must work with the standard equipment possessed by every Spectrum user. Electronics was out — tape scramblers, ‘dongles’, ROMs and so forth are expensive and hard to manufacture in bulk. The solution was to use the only part of the system that had not yet been harnessed against illegal copying — the TV set.

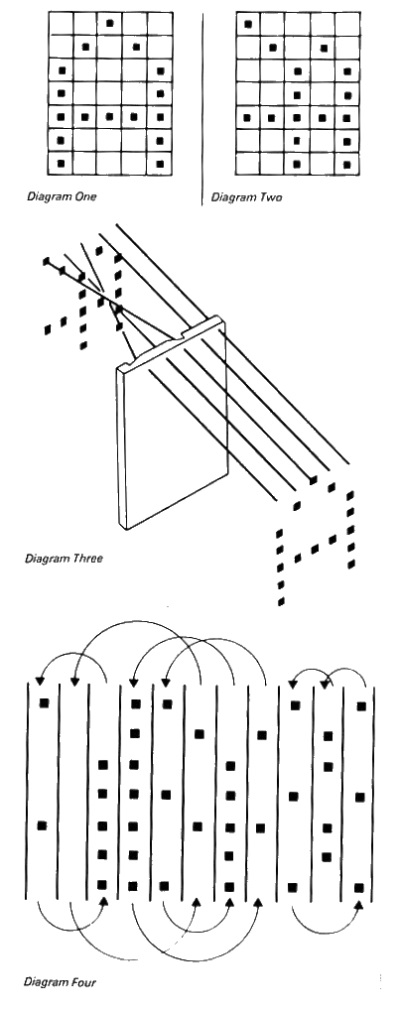

TV’s and micros both work by displaying a pattern of small dots which look like pictures, or text, when viewed from a distance. The first diagram shows the way a letter A might be represented as a pattern of dots.

Wedge-shaped transparent plastic prisms can be used to deflect light. Take the pattern of dots in the figure A, in diagram one. If you look at a same pattern through a group of narrow prisms, the columns can be swapped around — as light passes through the arrangement of prisms, the order of columns can be scrambled, so that they don’t form a pattern representing a recognisable character. See diagram two.

The columns are always swapped in the same sequence by a given group of prisms, or ‘lens’, so it follows that a lens used to scramble the dots which make up a letter can be used to un-scramble a pattern of dots produced by swapping the columns in a letter, providing those columns have been swapped round appropriately. This is shown in the third diagram.

This principle forms the basis of Lenslok, an optical ‘key’ invented by a new firm called ASAP Developments. (Indeed, the diagrams used here are taken from their brochure — with thanks.) Lenslok is used on new Spectrum programs like Elite. Interestingly, Firebird also use headerless files in Elite, which will make Microdrive owners legitimately angry — yet again they have to resort to subterfuge to get their games to load onto Microdrive. One would have thought that Lenslok protected their Microdrive copies just as well as their cassette. Perhaps this ‘belt and braces’ approach is a sign that Lenslok has weaknesses...

Anyhow, Elite displays a scrambled pattern when it is first loaded. If you look at the pattern through the lens you see two characters, and you have ten seconds to type them at the keyboard. If you’ve not got the lens all you see is a jumble of dots. If you can’t type the correct characters within three trys — and there are hundreds of possibilities — the computer resets and you have to re-load the program before you can try again.

Two characters are used, rather than one, since this makes it much harder to guess the correct code — there are more possibilities and the columns which make up the two characters can be inter-mingled. Some columns on the screen are not visible through the lens at all, so it is difficult to recognise the patterns by eye, especially when you only get ten seconds to think about it! Diagram four shows the way that two characters can be muddled together.

There are millions of possible ‘scrambling’ patterns, so that a different scrambling routine, and hence a different lens, can used for every program. It’s no good trying to use the lens supplied with Elite to get started with Digital Integration’s Tomahawk, for instance...

The lenses can be moulded in one piece from polystyrene (like parts for model kits) so they can be economically produced in small numbers (but not on the kitchen table); a few thousand lenses cost less than 20p each. Each lens comes in a holder which fits inside a cassette box — there are even holes for the prongs which hold the cassette spools.

However, display units vary enormously — the rich and famous have crystal clear monitors, some people have old 26 inch tellies, some use black and white portables and so on. Lenslok has to cope with every possible variation, with the exception of Uncle Sir Clive’s Microvision, which luckily doesn’t have an aerial socket!

The answer is to let you scale down the display to suit your TV. The Lenslok software displays a pattern which can be expanded or contracted to match the width of the lens holder. In theory, the computer can use this to work out the size of your telly, and hence the width of each column in the scrambled pattern — the bigger your TV, the less dots there will be in each column, since the display must be the same physical size on any set if the lens is to work.

I say ‘in theory’, because I found that in the case of Elite, the lens worked best when the pattern was set up rather wider than the lens holder; but this wasn’t too much trouble since, like most people, I treat instructions with healthy scepticism! As part of the set up routine, the computer displays the pattern for the letters "OK" as you expand or contract the display, so it is easy enough to set the right size by eye.

There are a few pitfalls for the unwary; the lenses don’t work unless you look directly into them, so you can’t use them properly if your TV is on the floor or on a high shelf. They don’t work if you’ve got both eyes open, and they have to be lined up quite carefully to avoid distortion of the image.

That said, Lenslok is a major step forward in the Spectrum software market, because it is an effective way to dissuade tape-to-tape copiers. It remains to be seen whether or not Lenslok will make a major difference to the amount of copying that goes on — Elite is not much fun without the instructions anyway — but if it does, that’s good news for everyone that buys software.

Micro software is becoming more and more sophisticated and development costs are going up and up. Some of the best ideas never make their way into code because they would cost more to develop than could be recouped from sales — if the pirates take their cut. Effective software protection, at a low cost, ought to bring down the price of top software. It could also encourage software houses to produce some of the special purpose programs which never see the light of day at the moment.

Don’t turn a blind eye to Lenslok!