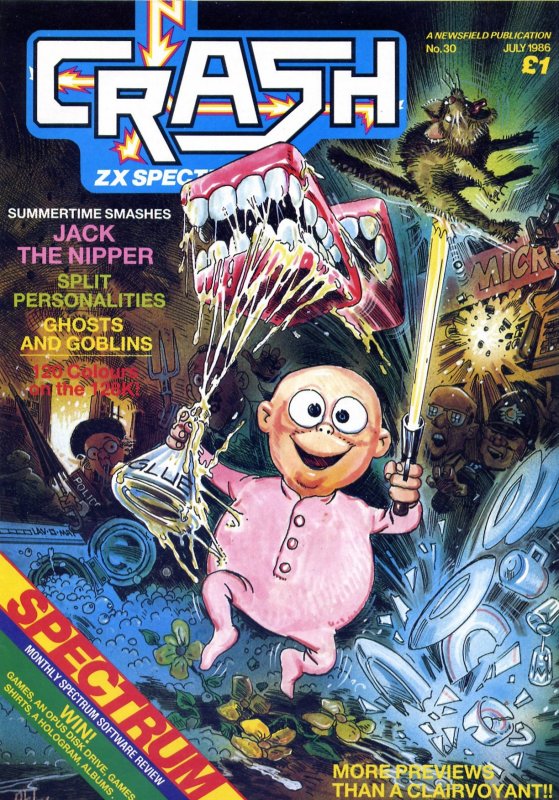

It’s not a reflection on the game it portrays, Gremlin Graphics’s Jack The Nipper — but of all the covers he has painted, this remains the one Oliver hates the most. Its subject matter runs counter to everything he enjoys illustrating. His strength lies in action, strong composition and powerful figure work. For days he was despondent at the thought of a benappied infant on a CRASH cover, and how he was going to do it. Under protest, at the last hour, he penned and coloured it, and it was a creditable effort.

It was an indication of how ‘professional’ the organisation was becoming when, in the middle of June, the management sat down to design the Newsfield stand for the forthcoming PCW Show. Previously, the magazines’ attendance had been a case either of wandering round or of restriction to something resembling a long table with hand-lettered signs. This year, we were told, there would be a proper stand built by a contractor. Gosh, were we excited. But that was ages away, so who cared?

Rather more to the point was the argument about the spelling of ‘magic’. Gargoyle Games had insisted on Heavy On The Magick, now Level 9 gave us The Price of Magik. Derek Brewster did not enter into the discussion, preferring instead to award Level 9 a Smash. He must have been pleased, not so much because good adventures had been a little thin on the ground, but because there were fewer and fewer full-price adventures appearing. The trend would continue, and today the majority of 8-bit adventures are provided through mall order from committed individual programmers.

Besides The Price Of Magik we had Jack The Nipper, which created yet another cute character for Gremlin Graphics’s repertory company of cute characters and got its Smash for being highly playable, entertaining and having ‘masterful graphics’. Then there was Ghosts ’N Goblins, awaited with bated breath — would the popular Capcom coin-op be a success or a flop for Elite? They pulled it off, and Ghosts ’N Goblins was one of the best conversions from an arcade original yet seen. And finally, just to prove they could do it, Domark came up with Splitting Images, not a TV tie-in, but a block puzzle based on caricatures of the famous. It was irresistible and gave Domark their first ever Smash.

Licences were in the doldrums again, apart from Ghosts ’N Goblins, for Mirrorsoft’s game version of the film of Biggles was very disappointing, not very innovative and consisted of three poorly-implemented subgames — it was rather like the film, in fact. And US Gold got themselves into terrible trouble with mistimed World Cup fever. It was almost instantly clear to us that the much-hyped World Cup Carnival was a minutely modified version of Artic’s two-year-old and forgettable World Cup Soccer. It cost £9.95, though remaindered versions of Artic’s original were to be had for £1.99. Retailers, distributors and buyers reacted as one in an outcry. Later, US Gold was forced to admit that they had planned a far better game, but programming delays and marketing problems had overtaken them. Timing was of the essence and in the end a decision was taken to buy and repackage the Artic game instead. In a way it provided a perfect example of what, at the worst, was so wrong with licensed and endorsed games. At best it was misguided, at worst it was seen by the public as a cynical attempt to pretend an old game was something new and get everyone to buy it all over again for the sake of a few bits of added packaging.

Quietly, in the midst of this, veteran software house New Generation pushed out the Spectrum version of Cliff Hanger, a sort of cowboy forerunner of Road Runner. It was a moderately enjoyable game, notable most of all for the fact that the advert told a story; cheques and postal orders were to be made payable to Virgin Games. It was to be New Generation’s last fling before quietly disappearing.