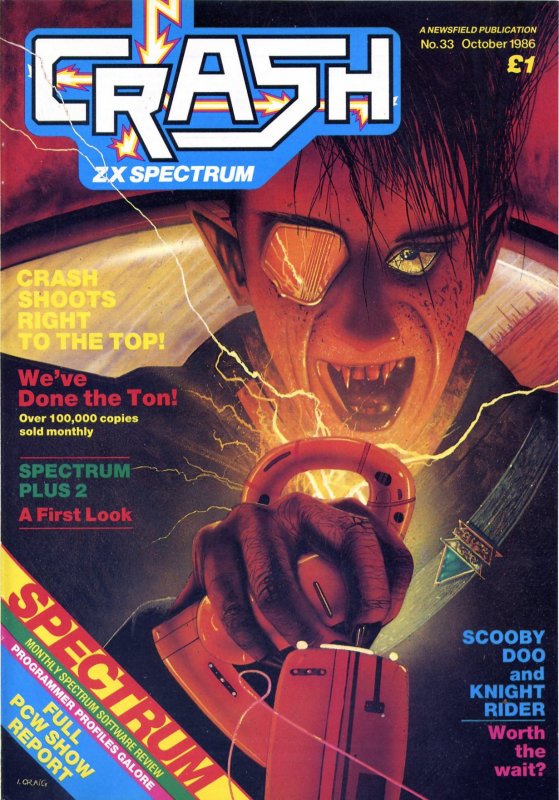

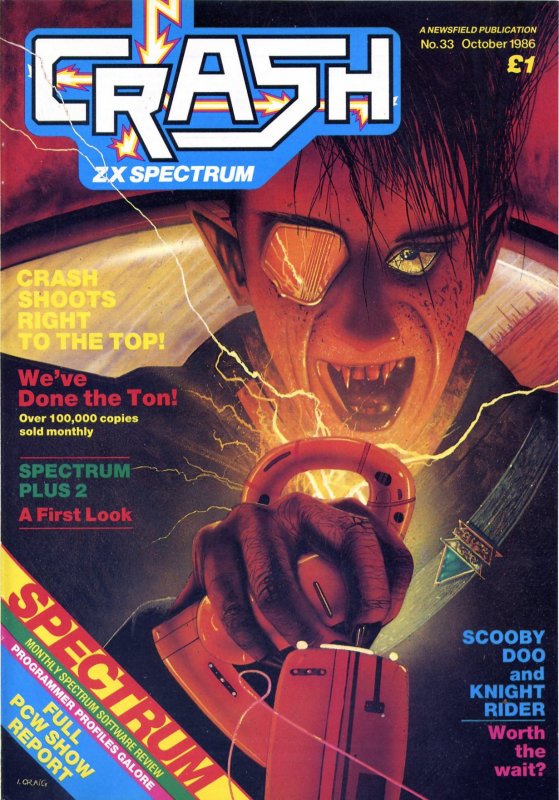

October’s cover marked a departure from the previous 32 covers; for the first time in the CRASH history it was painted by a hand other than Oliver Frey’s, that of Ian Craig. It was not designed with any particular game in mind, but did have a passing resemblance to (and was a visual pun on) Oliver’s very first CRASH cover. For the savage face, Ian used a photograph of a friend, though the pointed ears and sharp fangs were invented. As Oliver does with many pictures, Ian used an airbrush and then overpainted with an ordinary brush.

Early in September most of the editorial and mail-order staff decamped to London’s Olympia for the ninth PCW Show. It was the year of the infamous sticker campaign, when C&VG plastered the Newsfield stand with Melissa Ravenflame adhesive labels, and Newsfield retaliated with some Hannah Smith stickers printed at the last moment. At one point, Commodore User editor Eugene Lacy returned to the EMAP stand’s office and could no longer find the door — Mike Dunn and Ben Stone had hidden it under literally hundreds of stickers.

It was also the moment when Gargoyle Games underwent a metamorphosis and became Faster Than Light. Apart from the excitement of their own two games, Lightforce and Shockway Rider, they had a hit on their hands for Elite with the much-delayed Scooby Doo. Elite were riding high: after a disappointing Commodore 64 conversion of the coin-op Paper Boy, it only just missed a CRASH Smash on the Spectrum, though the Capcom conversion 1941 did far less well. Domark followed up the puzzles of Splitting Images with the official version of Trivial Pursuit. Despite the many trivia clones already out, the qualities of Domark’s version shone out, and it too received a Smash. We also thought highly of Costa Panayi’s Revolution, a 3-D puzzle-solving game which earned Vortex yet another in their long line of Smashes.

The biggest disappointment, though hardly a surprise, came with Ocean’s ludicrously delayed Knight Rider. Rumours from within Ocean’s offices had said it was a poor effort, and it was.

Internally there were some sweeping changes. The new offices opened, admin moved out, film planning moved down, LM moved across for two weeks from its small room into what had been advertising before finally departing to Gravel Hill, CRASH moved upstairs to where LM had been and Cameron Pound’s photographic empire gained the room CRASH had just vacated. It was a bit like playing Splitting Images.

Graeme Kidd waved a goodbye of sorts. At the very end of August, shortly after CRASH’s new Staff Writer Tony Flanagan had decided to leave, Graeme himself resigned over administrative problems. It was a difficult moment, with CRASH short-staffed and LM starting up, so Graeme was offered a new job as Publishing Executive in overall charge of the three computer magazines — which he accepted. However, he would remain titular editor of CRASH for a while yet. Meanwhile, Roger Kean had finally relinquished the editorship of ZZAP! to Gary Penn, and moved with the rest of LM to their new home in Gravel Hill. It was a busy month.

And on top of that came news from the Audit Bureau Of Circulations that CRASH was still the biggest-selling computer title in Britain, outstripping all others at over 100,000 copies a month. Roger Kean recalled a meeting in April 1984 with several top people from the old Imagine in Liverpool, when someone prophetically told him that CRASH was so different that it was bound to sell over 100,000 a month soon. He had been pleased, but seriously doubted CRASH would ever reach those sorts of figures. Doing better than 50,000 would have been a thrill for us in those early months.

At about the moment the October edition reached the printers, LM was officially launched at a big party in London, where the dummy was introduced to potential advertisers and Roger Kean made a speech he had rehearsed for days. I hate parties, I didn’t go.