Compared with the great rain clouds that drift through our lives, sexist computer games don’t even rank as a drizzle — Ian Phillipson

Are games unfair to the fairer sex? IAN PHILLIPSON and KATI HAMZA give opposing views on the sexism-and-censorship debate

Compared with the great rain clouds that drift through our lives, sexist computer games don’t even rank as a drizzle — Ian Phillipson

Censorship is an ugly word. It means controlling, or preventing, what others say, do and see. In some instances censorship is necessary — in most it is not.

The word once conjured up images of people fighting for fundamental rights that affected their way of life and that of future generations. But in recent years the word has become trivialised, and it’s used every day to describe almost any kind of control.

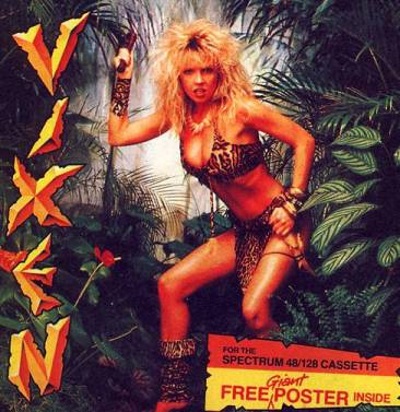

Boots’s decision that their shops would not sell Martech’s Vixen unless the inlay artwork were changed has brought into sharp relief the whole question of censorship and the computer game. And the issue here isn’t just censorship — it’s sexism.

‘Sexism is judging people by their gender, where it is irrelevant.’ Probably very few people would stand up and justify sexism, but is it an area to which censorship should be applied quite so readily?

The percentage of ‘sexist’ mainstream games released in a year is small. Indeed, compared with the great rain clouds that drift through our lives, the problem of sexist computer games doesn’t even rank as a drizzle. The fact is most people don’t give a damn whether computer games are sexist or not and would regard videos and TV as far more important factors in creating and reinforcing sexist attitudes.

But if the procensorship lobby must make a fuss and have their pound of flesh, by insisting that censorship in some form or another is imposed upon the industry, how are they going to make it work?

The strongest response is a typical kneejerk reaction — if you don’t like something, pass a law that prevents it. In an undiluted form this would state that you just cannot be sexist.

But laws are only effective if people think they are good laws, worth obeying, and if there are prison sentences and fines to reinforce them. So sweeping censorship of that kind would soon bring the law into disrepute.

Inevitably, most prosecution cases would look silly (the latest antics of borough councils who discipline employees for using words such as ‘luv’, ‘dear’ and ‘gorgeous’ are proof of this).

And many games producers would unwittingly fall foul of someone else’s interpretation of sexism — so often that they’d never be out of court. The courts would become full of ‘criminals’, and all because a relatively small number of people thought there was a problem.

The legislation couldn’t just cover computer games — to be fair (or unfair) to all trades alike, censorship would have to be applied to the toy industry, the publishing world, and music business, anywhere sexist ideas could lurk.

If legislating against sexism is not a good route, what about setting up a watchdog committee which decides what is allowable and what is not? This is the system adopted by TV in the form of the IBA, the BBC’s governors and now the Broadcasting Standards Committee. All rule upon viewing tastes, and judge the inherent violence and sex of programmes screened.

If such a committee were set up for software, not only would it be underworked (there are comparatively few blatantly sexist games), but it would also have to be given teeth. Otherwise it would become like the Press Council and Advertising Standards Authority, the two bodies set up to deal with complaints about newspapers and magazines — they can rap knuckles, but not much else.

Such a committee would have to be able to impose fines or sanctions on companies found guilty of producing sexist material. Ultimately it could throw them out of trade associations and the like, but even that would only be effective if the associations were worth joining in the first place.

Perhaps such a committee would be more useful (and even this is a very debatable point) considering violence in computer games. It might be more helpful than pondering whether a pixel-imperfect Amazonian beauty baring her bosom on a few inches of video screen, or on packaging, stereotypes all women as sex objects and inflames male passions.

The third choice is to work to a voluntary code. This is a better option and it could work, but the emphasis would have to be upon the word ‘voluntary’. If games producers didn’t want to abide by it, they wouldn’t have to, and no-one could stop them.

But of course, there’s already a kind of unwritten voluntary code, called taste — few software houses would consider rape or child molestation as suitable subjects for games.

So the fourth course is to leave things as they are. On the face of, perhaps this can be seen as an abdication of responsibility, but I would argue that it is the best choice of all.

Tolerance should be shown to what others do, even if you don’t like it. That it is a fundamental principle of democratic societies and you shouldn’t stray too far from it.

More importantly still, there is no need for an imposed form of censorship — simply because a system of censorship is already in existence and for the most part it works effectively.

If people don’t like the inherent sexism in a game or its packaging, people don’t have to buy it. They can raise their objection by leaving it on the shelf. Market forces are a far more potent power than any legislation in changing attitudes.

If large retailers and distributors — or a sufficient number of smaller ones — refuse to distribute or sell games that they find sexist, such games will cease to be produced. No company wants to lose money.

This is the line Boots seem to have taken over Vixen.

And at last the software shops won’t be incurring the wrath of a flock of fatherly Mr Angries from Purley. Of course, they’ll be doing a page 3 Luvly out of a job -but, as they say, that’s another ball game.

Be honest — the first thing you think of on seeing a Vixen ad isn’t Corinne Russell’s brain! — Kati Hamza

There’s nothing wrong with flesh. The naked body is just as beautiful and just as worthy of respect as one covered up with clothes.

The more extreme members of the procensorship lobby might not agree. Their argument reaches right back to the Old Testament: when Adam and Eve ate the apple from the Tree Of Knowledge they covered up their genitals with fig leaves.

So, the supporters of censorship argue, a naked human being, male or female, should only be featured in TV programmes, films and computer games under special circumstances — and certainly not before 9pm!

Fortunately, in our enlightened society, extreme censorship isn’t gaining a foothold. In Britain, the system is fairly low-key and moves to change it are met by controversy. Freedom of the press is valued as a vital democratic right.

After all, a democratic government insists ‘on equal rights and privileges for all’. Working on the principle that everyone has a right to vote, it assumes that everyone is prepared to accept personal responsibility.

According to the law, that responsibility doesn’t come until you’re 18. At 18 you can vote, buy a drink in a pub, visit porn shops and read girlie magazines to your heart’s content.

But polls in CRASH and ZZAP! 64 have shown that most people who play computer games — and could be subjected to potentially sexist advertising by software houses — are under 18.

The publishers, advertisers and retailers are all adults, so they should have some responsibility to the underage consumers of their products. That’s not to say that young people are idiots or can’t think for themselves, but that because they are not yet set in their ways they tend to be more receptive to the influences around them.

When it comes to the portrayal of women, a lot of the influences are negative. It’s true that male/female stereotypes are dying out: women are no longer expected to be housewives while their men bring home the bacon, girls have the right to exactly the same education as boys, and employers are forced by law to give women and men the same pay for the same jobs.

These are huge steps in the right direction, but you only have to look around you to see that sexist conditioning still prevails.

In school, more boys take science subjects than girls. In certain areas of business, it’s far more difficult for a woman to progress than a man (though the reverse is also true). More women than men are subjected to sexual harassment at work.

From infancy onward, women are given the impression that they are the weaker sex. It’s considered more appropriate that a girl should back down in an argument; boys are taught to be aggressive.

You’ll often hear children of both sexes say that their mother is ‘only a housewife’.

A promiscuous man is more socially acceptable than a established promiscuous woman: he’s branded a playboy, she a slag.

These prejudices aren’t always blatantly expressed, but their influence is subtle and runs deep. If you’ve lived in a society all your life, you tend to absorb its general opinions without necessarily questioning them. Our earliest experiences and impressions are the most deep-rooted and they’re pretty hard to shake off.

If you’re a 14-year-old boy and you own a computer, you could be playing games for up to five hours a day. The presentation of women in many of these games and the advertising associated with them is hardly flattering. Barbarian had to rescue a pretty pathetic Princess Mariana, and the victim of Mermaid Madness couldn’t get away from his beloved quick enough because she was so ugly!

The advertising for these sort games relies heavily on scantily-clad females — who don’t always feature very much in the game — chosen only for their sexual appeal. More often than not, the image they create is totally irrelevant to the product.

Again, it’s not the bodies themselves which are unacceptable but the way in which they’re portrayed. The implication is that there’s nothing more to women than bodies and that all they’re there for is sex.

Be honest — the first thing you think of on seeing a Vixen ad isn’t Corinne Russell’s brain, is it?

Nobody’s arguing that a sexist poster is going to make you treat every woman with disrespect, merely that the way in which it portrays women serves to subtly reinforce sexist attitudes which still prevail.

Working on the democratic principle that everyone has the ability to make up their own mind, we like to impose as little organised censorship as possible. Effectively the moral burden is transferred to the individual. The individuals in this case are the directors and employees of the software companies, the publishers and the retailers.

Already there have been some changes. A few games let you choose between a male and a female character: after the controversy over Barbarian, Palace’s Barbarian II features Mariana in an equal rather than a subjugated role. Boots have refused to sell Martech’s Vixen with the provocative picture on the cover.

Without intervention from any organised body, the moral burden is transferred to the individuals responsible enough to deal with It. Boots have already shown that they’re prepared to accept that responsibility; it remains to be seen whether other companies will follow suit.